Yes, you should go to Nagasaki

What makes the NYT travel pick such a special city

I’ll be in the hillside community of Shioya in Kobe on February 14-15 as part of a two-day event on local urbanism. On the afternoon of 2/15, I’ll be introducing my work during a two-hour talk (in Japanese). If you’re in Kansai, please take a look at the details above.

Nagasaki, one of my favorite cities in Japan, appears at #17 on this year’s New York Times’ 52 Places to Go List. In his newsletter explaining why he chose Nagasaki (following previous picks of Morioka, Yamaguchi, and Toyama), Craig Mod also mentions that I had something to do with it landing there:

I’ve been to Nagasaki five or six times over the last twelve years, and it’s always felt like a special place, but it wasn’t until I was having coffee with Sam Holden a few years ago, that his passion (he’s a verifiable Nagasaki (and Onomichi) maniac), for the city inspired me to take an even deeper look. So I went back, and it was, indeed, great.

Needless to say, as a “verifiable Nagasaki maniac” I think the city deserves more attention from discerning travelers. I first went to Nagasaki a month after I moved to Tokyo in 2014, and have been back about every other year since. In 2024, Craig and I were chatting about his New York Times power, and knowing the sorts of places he likes to highlight (mid-size, somewhat out-of-the-way cities), I put in a good word for Nagasaki. So, hooray!

Despite being #17 on the list, two of my favorite spots in the city, the 800-year-old camphor tree at Daitokuji and the classic kissaten Fujio, show up in the first line of the NYT’s announcement of the list on Instagram. Are Americans so Japan-obsessed that the editors look at a list of the entire planet and just reflexively put them at the very top??

A quick aside before I get to Nagasaki—I am an advocate for camphor tourism: you should also visit this 600-year-old in Tokyo, this 900-year-old in Onomichi, this 2,600-year-old on Omishima, this 2,100-year-old in Atami, these 1,000-year-olds in Osaka and Nagoya, and this 700-year-old that endures at the middle of a railway platform (lovingly illustrated by Patrick Lydon). Sit down for a while, look up at their grandeur, read with them. Pray to them. A place always feels more magical after paying respects to one of the ancients.1

What makes Nagasaki special

Nagasaki’s charms are rooted in its geography and history. Nagasaki is very hilly, and as a general rule, hillside cities are among the most interesting places in Japan. Uneven topography preserves local distinction and human scale, while flat cities often suffer from the homogenizing effects of car-oriented sprawl and large-scale development. I have written about my love for Japan’s hillside communities here:

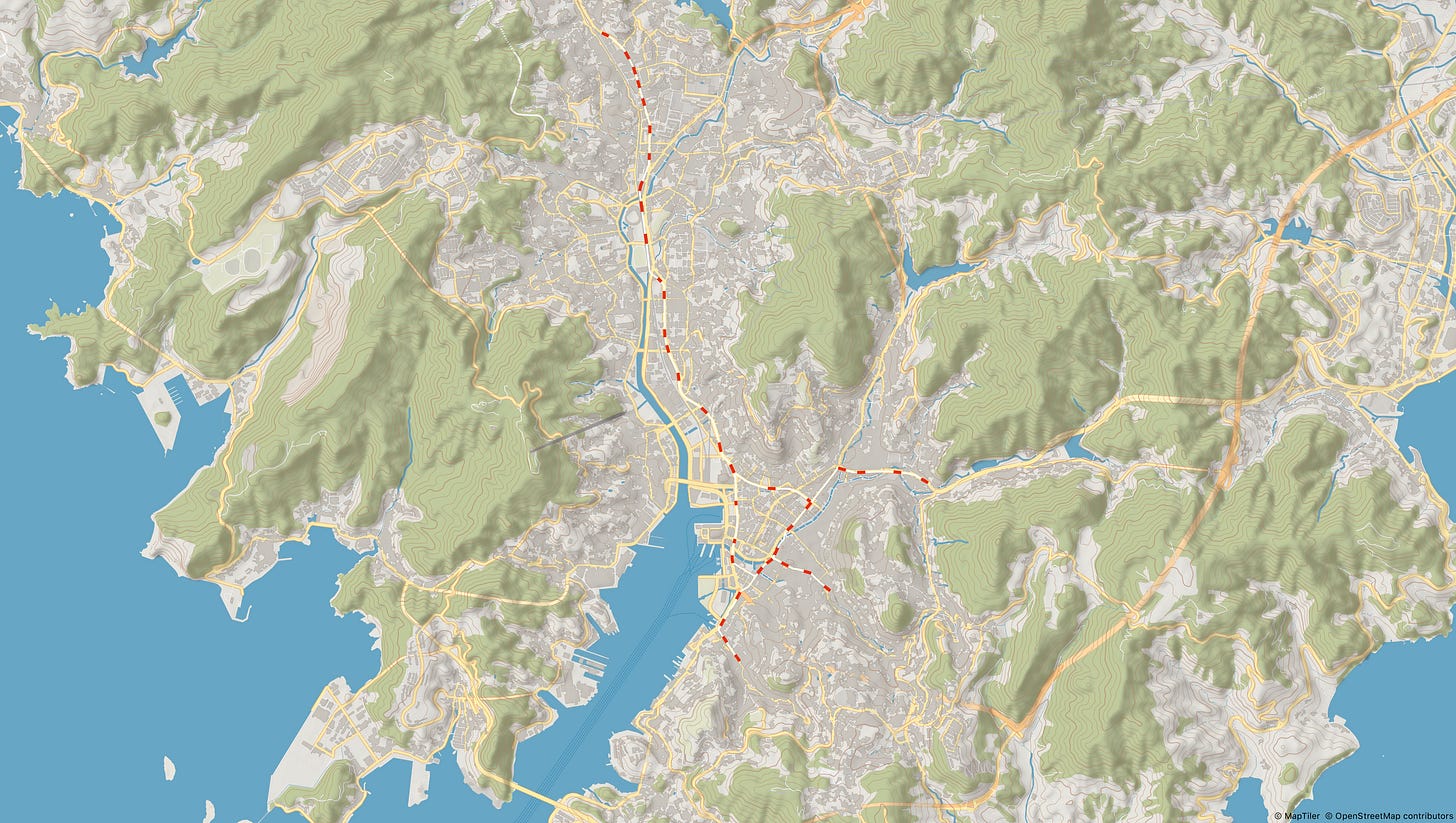

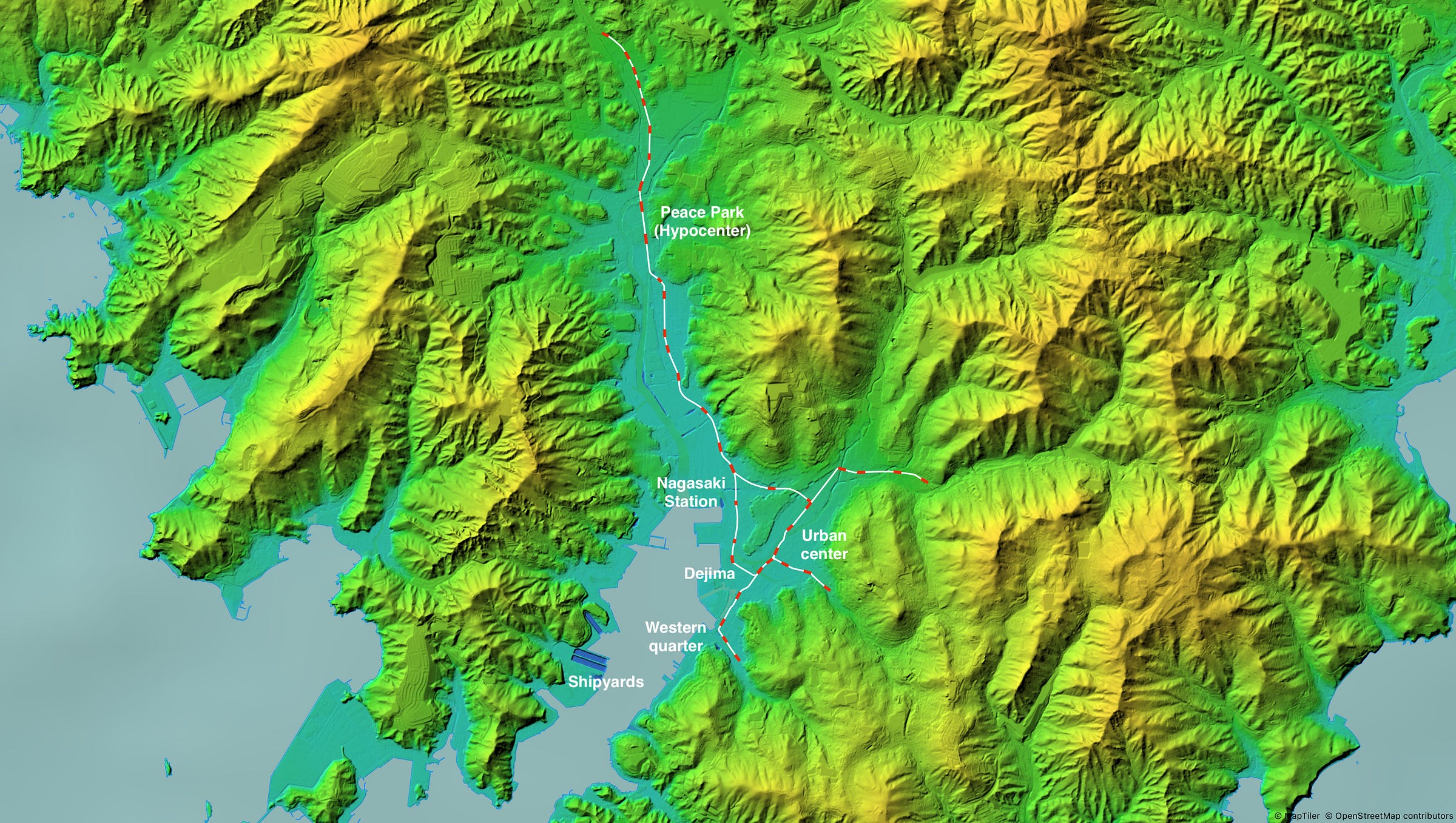

The urban area of Nagasaki (pop. 390,000) is centered on the valleys of the Urakami River and Nakashima River that feed into Nagasaki Harbor, and reaches high into the surrounding hills (while some hillsides are Onomichi-like areas where houses stand on narrow alleys with no car access, many are accessible by roads and buses and even diagonal elevators).

A contour map reveals just how little flat land there is, and how the streetcar system (white lines) provides a comprehensive network connecting the valley floors. On the streets, you’ll notice hardly anyone rides bicycles because it’s more logical to rely on the streetcars and walk or take motorized transport uphill (below you can also see the city’s primary industry across the harbor—those blue rectangles are the dry docks of the Mitsubishi shipyard, which has been around since the Meiji era).

Nagasaki’s growth has long been constrained by its mountainous topography and remoteness in far-western Japan. Over the past 70 years, the prefecture has had one of the fastest rates of population decline as people move to Tokyo, Osaka and Kyushu’s increasingly unipolar center in Fukuoka. While the city is somewhat insulated by its role as the prefectural capital, its population has declined by more than 100,000 since the 1970s. Many of the hillside areas are emptying out—I wrote about exploring one area of abandoned houses with a group of local akiya activists during a visit in 2015.

Even so, Nagasaki feels lively, in part because in an age of shrinking cities, its challenging topography also works to its benefit by concentrating urban vitality in a small, walkable center. Shrinking municipalities across Japan have tried to implement “compact city” strategies to maintain vitality in the face of not just population decline, but also the car-oriented suburbs, shopping malls and large-scale roadside retail that have hollowed out downtowns and shuttered shopping streets. Nagasaki is a natural compact city, with a bustling shopping arcade in Hamamachi, an active nightlife district in Shianbashi, and a contiguous urban fabric with relatively few parking lots.

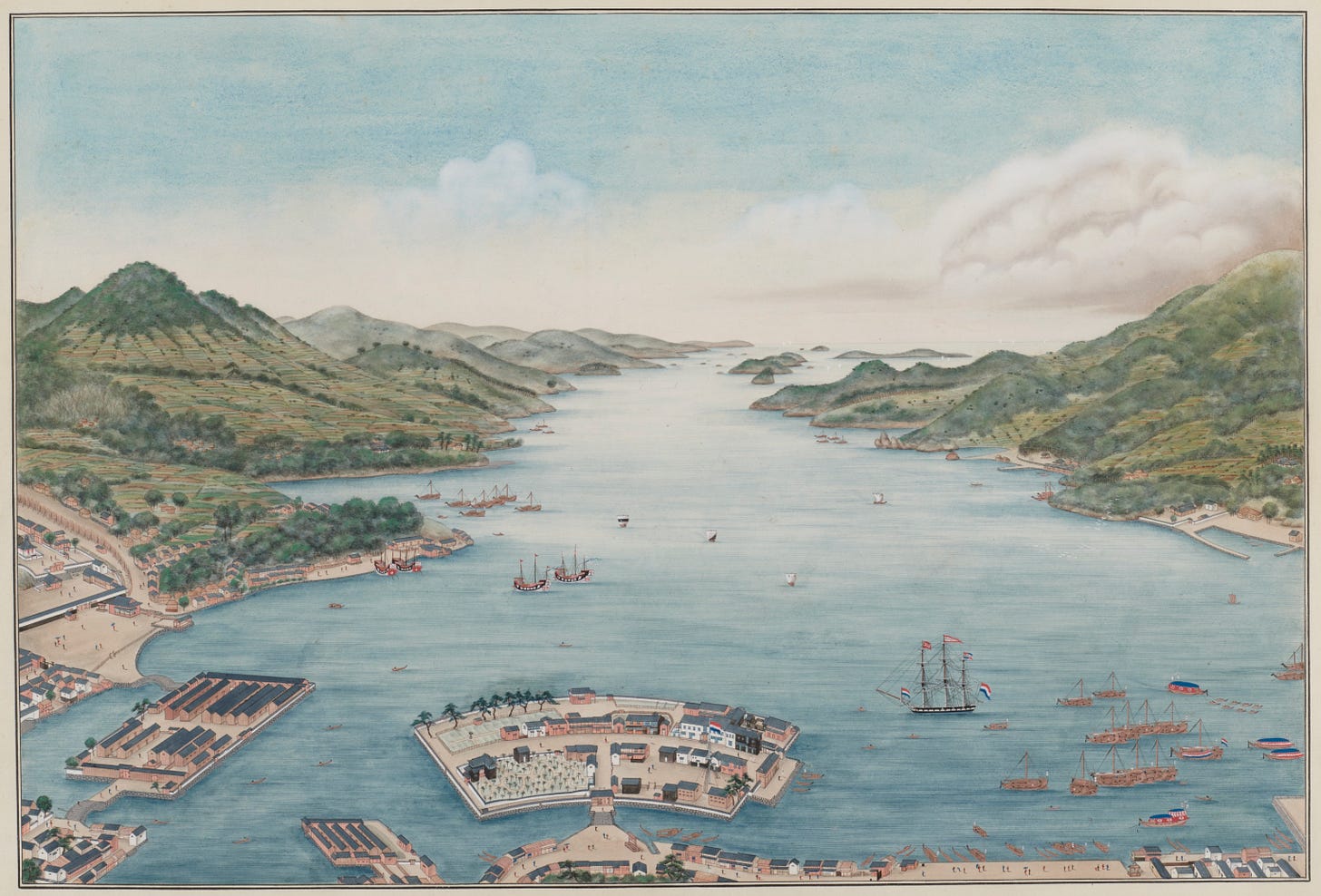

Geography is also why Nagasaki has such an interesting history—the natural harbor in a distant corner of the country was a good place to isolate contact between Japan and the outside world during Japan’s era of closure from the 17th and 19th centuries. Dutch traders established an outpost on Dejima, an island just off the shore, while a Chinese quarter (Tojin-yashiki) existed nearby. Today, Dejima’s buildings have been reconstructed and contain good exhibits that convey this episode of global history. Later, when the country finally opened under Western pressure in the 1850s, Nagasaki was chosen as one of the five ports open to foreign ships. The heritage of this second era of Western influence is most concentrated in Minami Yamate, the old foreign quarter on the hillside overlooking the harbor. The 1864 Oura Cathedral, Japan’s oldest church building, has several memorials to Christians who were persecuted and kept the faith in hiding before Japan’s re-opening (go to the Goto Islands off the coast to explore the World Heritage churches built by in “Kakure-Christian” communities).

Craig begins his recommendation with a call to contemplate the city’s atomic bombing at a time when nuclear weapons are again a menace. Nagasaki’s destruction at the end of World War II is surely the event that looms largest in the eyes of the world, but the city has always received a fraction of the focus directed at the city that was erased three days before it.

Largely, this is a function of Hiroshima’s misfortune of being first, along with its proximity to other tourist destinations, and the powerful visual symbolism of the A-Bomb Dome. Hiroshima is a great city that I visit every year, but I noticed when I took my dad there last October that the sheer volume of tourists (many probably there because the dome and Miyajima are all over social media) feels somewhat incongruous with quiet contemplation of humankind’s self-destruction. Visiting Nagasaki’s park, museum and memorial, which are located outside of the center of the city, is just as valid a choice if you want to grapple with the horror of the atomic bombings, even if people online might not immediately recognize your pictures (at the end of the war, Nagasaki did have an atomic ruin that matched Hiroshima’s Dome in its visceral symbolism. The ruins of Urakami Cathedral, which in a twist of fate was right next to the off-target hypocenter, were demolished in the 1950s and rebuilt).

Some remnants of the original cathedral were moved to the Peace Park, and smaller remains such as the one-legged Torii Gate at Sanno Shrine have been preserved. Sanno Shrine is also home to two beautiful camphors that miraculously survived the bombing to return to their original vigor. The Nagasaki Kusunoki Project has mapped 50 camphors and other trees in the area that survived the blast. Spend a quiet morning at the museum and memorial, and then walk through the city in search of some of these survivors.

Some recommendations if you go

Stay

There are lots of ordinary hotels, but if you want a taste of what hillside neighborhoods are like, Sakayado is an architect-led effort to create accommodations in a cluster of old, less accessible homes a short (uphill) walk from the Sofukuji tram stop.

Another comfortable option is ksnowki, a small two-room renovated hotel and cafe opened by a young woman and her family, who once ran a sento nearby called—complete coincidence—Kusunoki-yu (Camphor Bath)!2

If I were looking for a fancier place to stay, I would choose Hotel Indigo Nagasaki, which opened in 2024 in a renovated 1898 red-brick convent and orphanage in the middle of the Western Quarter in Minami Yamate.

What to eat and do

Be sure to eat a bowl of champon, the Nagasaki speciality of creamy soup with chewy noodles that was created with Chinese influence in the 19th century. This local cafeteria on the edge of the Edo-era Chinese quarter (different from the modern Chinatown) is a good place to try it. Squeeze into a little gyoza shop for a quick plate with the local salarymen or a canalside stall for oden or ramen. Fujio is a great kissa coffee; Nagasaki also has plenty of third wave coffee and a nice old-school English teahouse, too.

Go out in the old Showa-era drinking quarter of Shianbashi (“Deliberation Bridge”), where men were said to consider whether to cross into the pleasure quarter of Maruyama (home to the retro police box). I’ve been to a some great little izakaya, sushi and oden places here, but perhaps I’ll leave you to try your luck (save some room for a closer of onigiri at the end of the night). Shianbashi won’t be around forever as many of the buildings stand over a buried river and don’t meet code, but for now, the vibes remain excellent.

If you’ve been to Hiroshima and are expecting the historical rupture of 1945 to be similarly total, you will be surprised by how much of the historical landscape remains, and not just in Dejima or Minami-Yamate. The temples of Teramachi-dori at the foot of the hills make for a great walk. Start at Yasaka Shrine and Sofukuji Temple, with its Ming-style architecture and this most exquisite tsukijibei wall.

As you walk, wander up the steep slopes into the hillside cemeteries and temple grounds. Then head across the river and up the grand staircase of Suwa Shrine (along with Yasaka Shrine, one of the locations of the annual Kunchi Festival), maybe stop for udon or sweets near the top. Return along the Nakashima River, crossing the many graceful stone bridges, including the city’s icon of Megane-bashi, dating from 1634.

For books, visit Hitoyasumi Book Store or Books Leiden. For gifts, go to Tatematsuru on the Edomachi Shotengai just outside Dejima. For textiles and ceramics, visit List or coffee & clayworks Kasa.

Wander the hills in search of cats, go see what’s growing on some of the community farm patches that my friend Hirayama has started on vacant hillside land. Go to an exhibition at the prefectural art museum, then grab a beer on a terrace at Dejima Wharf and watch the sunset across the harbor. Rent a car and go ceramics hunting in Arita (be sure to drop by my friend Sanae’s wonderful tea shop).

Kunchi Festival

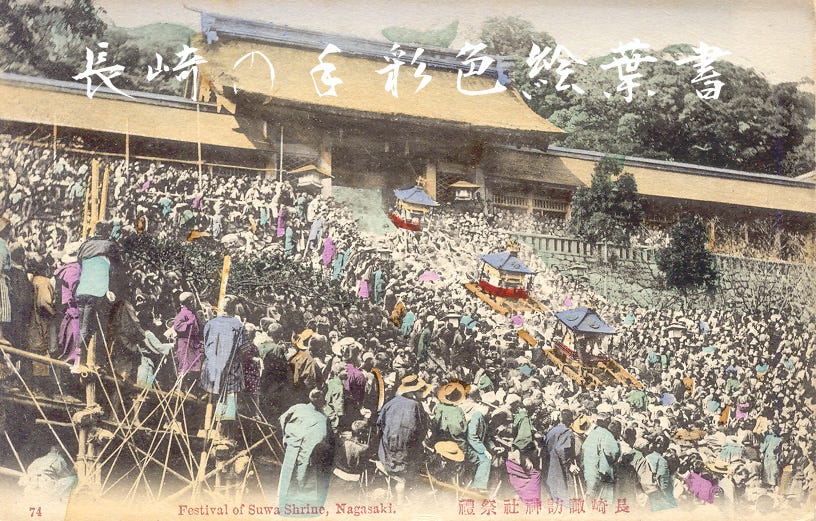

If you can, visit during Nagasaki Kunchi, the great festival that began in 1634 and takes place every October. Seven neighborhoods each have floats reflecting their local culture (or in the case of Chinatown, a dragon dance), and parade through the streets before gathering on the shrine grounds where they perform in front of spectators (then pull their floats straight down the stairs!).

Every seven years, each neighborhood takes its turn as the “odori-cho” (踊り町) and helms the festivities with a special performance. I owe my love of Nagasaki to my former classmate and roommate Kyohei, who grew up in Edomachi, the neighborhood just outside Dejima whose float is a Dutch galleon (alongside a smaller yellow one for the adorable children). When their turn came in 2019 and he was a leader of the float pullers, he invited me down to watch on the shrine grounds, where they arrive after making their way through the streets to spin the ship at high speed while percussionists bang their instruments on board.

Someday I’ll write more about Kyohei (now a member of city council) and my other Nagasaki friends who take so much pride in their home and have over the years shaped how I think about post-growth cities. For now, I hope some of you will take a few days for a visit. Nagasaki’s slow pace, small scale, and quiet beauty are an antidote to overtourism.

Like most good things in life, there is someone on the Japanese internet who has made an awesome blog about giant tree tourism, appropriately named https://bigtrees.life

Sadly, the lovely old sento I used to go to in Nagasaki, Nichiei-yu, closed down in 2024. Another good one closed in 2025. 35 sento in the 1960s have declined to just three. For those who read my last piece, there is, however, a fancy new sauna near the station redevelopment.

The compact city thesis here is really intresting - how topography basiclly does the work that urban planners elsewhere struggle with through policy. I've noticed this in some European hilltowns too but never made the connection to shrinking cities explicitly. The idea that physical constraints can actually become advantages when population declines is kinda counterintuitive. Makes me wonder if flat cities that invested heavily in sprawl infrastructure are going to have a much harder time maintaining vitality as demographics shift.

Nice. Already know I will like it. Planning a few weeks in the prefecture including the islands. Saved!