Osaka Airbnb-ification

Post-growth gentrification in the expo city

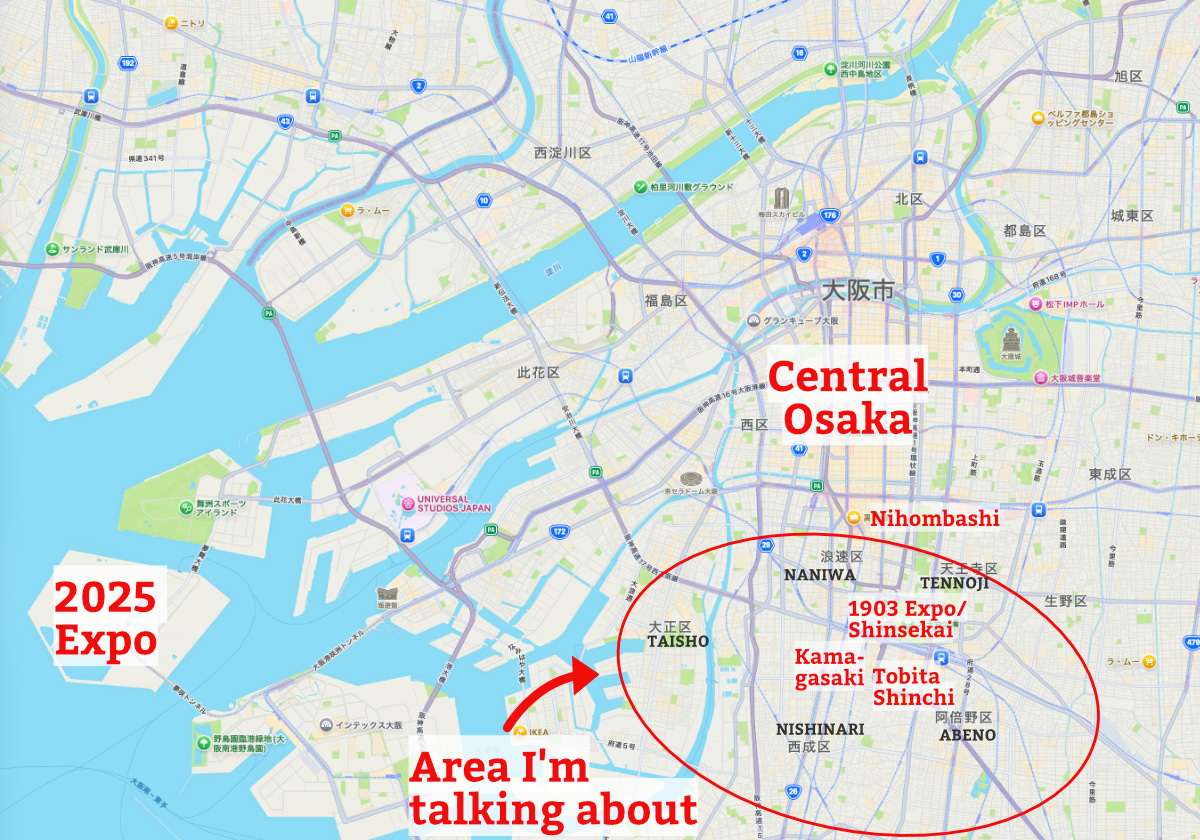

I stopped by Osaka in late September in order to see the World Expo before it closed last week. I haven’t seen many compelling critiques of the expo (just a few in Japanese, none so far in English), mostly because there is little interesting to say about the expo itself. Nonetheless, a mega-event is an opportunity to think about how urban geographies are shifting, and where narrative diverges from reality—a topic I’ll have an essay on soon.

With two days in the city, I also wanted to get outside of the central zone where most of the tourism boom and real estate investment is unfolding, and see how the current process of urban development interfaces with spreading desolation in the city’s post-growth areas. Walking and biking across the southwestern fringe of the city center (Taisho, Nishinari, Suminoe wards), I passed through many shuttered streets like the one below, where the expo flags stick out like something from far away.

The spillover of the tourist boom into these areas is sometimes referred to as “gentrification,”1 but this feels like an imprecise term to describe a process that is less organic (bottom-up social displacement) or bureaucratic (top-down urban renewal) than algorithmic.

Outside the bubble

Osaka’s top-line demographic situation looks strong: in 2024, it recorded the largest population increase of any city nationwide (21,387) and has added more than 200,000 residents since 2000 after decades of hollowing out. However, this influx has been concentrated in the six central wards popular with condominium developers, and coincided with the Kansai region’s population stagnation and now decline. Last year, Osaka also had the greatest natural decrease (deaths minus births) in Japan, and most areas of the city are losing population at an accelerating rate. Nishinari Ward has seen the greatest drop—its population of a little more than 100,000 has already declined 30% since 2000 and more than half from its 1960s peak, and could roughly halve again by 2050.

I stayed in Kamagasaki, an area of Nishinari known in the 20th century as one of the largest slums in Japan. As it so happens, the first time Osaka held an expo—not in 1970, but in 1903—an unsightly slum in the Nihombashi area blighted the main road from the city center to the expo grounds on the outskirts of Tennoji. To shield visitors from this unpleasant urban reality, the city cleared the slum, and displaced day laborers and other residents moved across the railroad tracks south of the expo venue, to what was then fields along the road to Wakayama. By 1970, 30-40,000 day laborers and dockworkers lived in Kamagasaki’s flophouses, and its hiring sites filled the 20,000-man daily workforce at the construction site for that year’s expo.2

Long stigmatized, the neighborhood has been passed over by redevelopment and remains home to many elderly ex-laborers. Their former professions are now the realm of non-Japanese workers, and the area’s foreign population has more than doubled in the past decade to around 10%—Chinese and Vietnamese are heard in the alleys, while African migrants congregate at night along the main street and in the entries of old apartment blocks. Abandoned and collapsing buildings are common. I peeked into the broken window of one building with a buckled facade, and spotted a stack of molding futon amid the detritus. But as one itinerant population fades out, another is taking its place—up and down the same street, the fresh facades of short-term rentals (below, Airbnbs) are now springing up thanks to that all-purpose tool of neoliberal governance known as the “special strategic zone.”

Osaka became a special strategic zone for short-term rentals in 2014, which relaxed various rules about Airbnb development and operation. The number has soared post-pandemic in the run-up to the expo. There are now around 7,000 short-term properties registered in the city under the “special zone” law—at least 1,700 of which are in Nishinari—along with many thousands more regulated under two other laws. News stories about residents getting pushed out, whole areas getting bought up by Chinese capital, or huge apartment conversions pursued without any explanation to neighbors have contributed to a sense that things have gotten out of control. The city has now frozen new approvals.

Market mechanisms have unsurprisingly led to widespread Airbnb development in Nishinari, where the real estate is a bargain for an area so close to the city’s main attractions. Foreign tourists are not entirely new here—backpackers have been showing up in the old doya-gai (flophouse) districts of Tokyo and Osaka since the mid-2000s in search of cheap accommodations. In Kamagasaki, the non-profit Cocoroom3 has long operated a guesthouse alongside a cafe and art space, where they serve meals to the community twice a day and travelers interact with Kamagasaki residents, including the homeless (their website’s lovely advice: “You might get into an awkward situation at times. If you do, just breathe deeply and be generous”). Some of the elderly locals at Cocoroom have even been known to take travelers along to hospital visits and funerals for their friends.4

Cocoroom is a special example, but until recently, entering into such an urban context as a tourist entailed a certain degree of agency and communication. Needless to say, this is not the experience of those who now arrive passively through algorithmic sorting and expect a frictionless experience that merely satisfies a balance of proximity to attractions and cost performance.

An Airbnb Experience

I figured I should see what the tourist experience is like. Before going to Osaka, I downloaded Airbnb and zoomed into Nishinari, then pinched further, to the area of Kamagasaki just to the east of the highway overpass. Pins popped up where they probably shouldn’t be—in the middle of Tobita Shinchi, Japan’s most brazen brothel district, where hundreds of sex workers sit on cushions in brightly-lit rooms lining the streets.5

I booked a bland listing for the decent price of ¥11,000. Reviews were mostly five-star one-liners about the “clean room and super friendly host,” mixed with occasional three-star reviews alluding to the presence of certain, erm, insalubrious activities next door. My super-friendly host immediately got in touch with an AI-generated message explaining the automated keypad check-in (after check-out, they appeared in my inbox again to remind me that if I liked the room, I should only give a five-star rating—that is how AirBnb works). The 8-story concrete building, built in 2023 by a local real estate company, looked like an ordinary apartment block, but was all short-term rentals and unconvincingly branded as a “hotel.” It stood next to a wooden brothel on the far southern edge of Tobita Shinchi, with the most direct route to the station and tourist areas straight through the middle.

En route to the sento (slums had lots of baths!), I felt like I heard more English from the madams sitting in the brothel entryways than the other time I walked through the area with a friend in 2015, although my memory is vague. I am more certain that last time there was no English announcement playing over the speakers at the public toilets near the entrance—Welcome to Tobita Shinchi. We hope to make your time in Japan extra special! or something like that. In another sign of the times, a posted notice explained that a new, higher price has been instituted for foreign customers, of whom a fair number (and surely some gawkers) were walking the streets.6

The next day, I explored the neighborhood. The area’s original housing stock is primarily low-rise wooden row houses lining narrow alleyways.

Airbnbs can be easily spotted by the signs posted near the doors. They were indeed everywhere, along dying shopping streets and in back alleys on either side of aging tenements. It seemed that most new construction in the neighborhood was Airbnbs. Branding was barebones—“Joy Inn,” “Edo Inn” (yes, in Osaka), “Green Inn,” printed on curtains alongside logos that appeared AI-generated. A frenzy was clearly underway to convert local space into something that interfaces with a global economy that runs on tourist consumption and financial speculation.

One under-construction project with around 20 black three-story units filled a plot next to a rusting and overgrown tenement with Abeno Harukas, the city’s tallest building, looming behind. When I passed by a second time in the evening, one door was propped open, and three men who looked to be the developer, owner, and contractor came outside, discussing details in Chinese.

I had imagined the Airbnbs would be concentrated in the north of Kamagasaki, close to the tourist sites and transit, but when I biked through more distant Tenga Chaya to the south, it was the same story—Airbnb signs everywhere, new properties going up with Chinese-speaking developers outside, interspersed with rusting structures, vacant lots, and barely surviving local shops. I found an entire block of Airbnbs adjacent to one tram stop—four single-family properties, next to a sizable apartment block that had also been converted.

When I posted some images on Instagram, an old friend who is now a public school teacher in Osaka messaged me. Her colleague used to live in Tenga Chaya, and not too long ago the landlord slipped a paper in his mailbox: the entire building will be converted to Airbnbs. If you leave now, we will pay ¥200,000. A few months later the real estate folks came knocking. They bumped up their offer to half a million after he protested. Ah, the small indignities that must be inflicted to strip mine the city for a quick profit! At 65% occupancy, an Airbnb in Nishinari should pull in upwards of ¥3 million a year, far more than a public school teacher pays in rent.

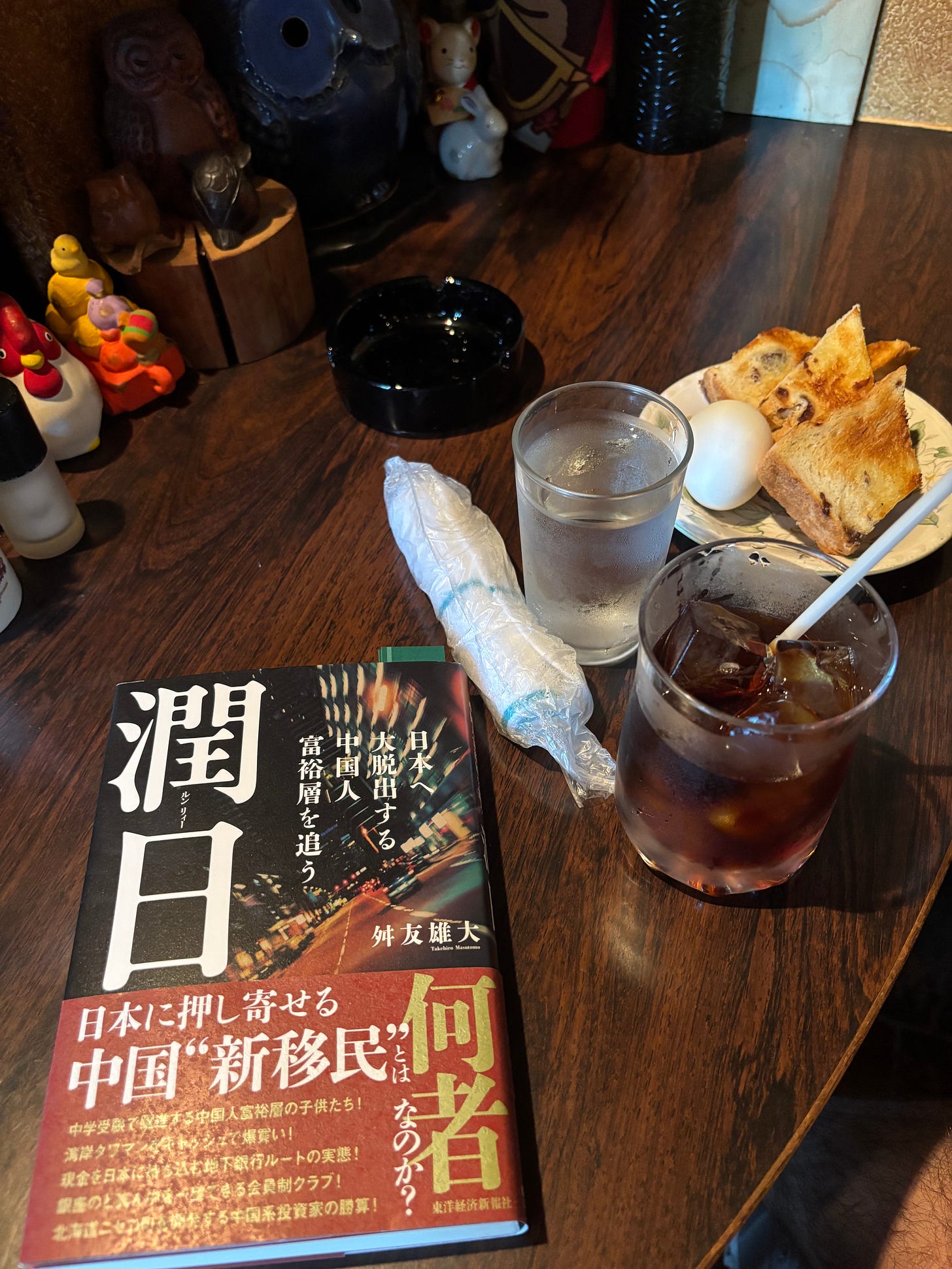

The “Run-ri” connection

While local real estate owners are certainly taking advantage of the tourism boom to cash in, notably about 45% of special-zone Airbnbs in Osaka are owned by Chinese investors. This capital influx is part of a post-pandemic trend known as “Run-ri” (潤日): wealthy mainlanders weary of instability at home who are seeking to relocate their assets and families to Japan. When I got off the Shinkansen in Osaka, I bought a copy of Masutomo Takehiro’s best-seller on the phenomenon, the main arguments of which are shared in the post below. The trend is having very significant local effects on parts of Tokyo, Kansai, Hokkaido and other places spotlighted by real estate consultants and influencers on Chinese social media.

Philip Brasor explains how the Osaka Airbnbs fit into the Run-ri immigration game:

When a Chinese person buys a property with the intention of making it into a minpaku [Airbnb], the Chinese person then registers themself as a business owner in Japan, even if they remain in China. They then hire a management agent to run the property; or, if they bought the property from a developer, the developer will manage it. Farther down the line, the Chinese owner may move to Japan after attaining a business owner’s visa, which requires only ¥5 million in capital [raised to ¥30 million=$200,000 this month]. They can then live in Japan, along with their family, indefinitely as long as they are registered as a business owner. Even farther down the line they can apply for permanent residency.

Many of the multi-unit developments I saw going up all over Kamagasaki are being used to secure visas, with owners then buying nice condos elsewhere in cash.7

One of the areas on the Run-ri radar is Bunkyo Ward—where I live in Tokyo. Bunkyo’s Chinese population has gone up from around 5,000 to 9,000 since 2022, accounting for more than half of the ward’s total growth, as Run-ri families snap up properties and spike prices near the four elementary schools seen as stepping stones to the University of Tokyo, which is located in Bunkyo. In a recent piece in the FT, Leo Lewis quotes a Chinese woman in Bunkyo who appears to adore everything about the neighborhood—except that lately “there are too many Chinese around” because of all the real estate influencers. Walking beneath the gingko leaves on the University of Tokyo campus is one of my favorite seasonal pleasures, but last year it was unlike I’d ever seen: rows of tour buses and black cars dropping off tourists outside the gates, while every few steps under the trees, young people appeared to be filming TikTok reels.

The Chinese real estate frenzy in Bunkyo and the Airbnb-ification of Nishinari are two facets of the same economic imbalance: local places at the disruptive confluence of algorithmic amplification, hyper-mobility, and global-scale wealth inequality. While the instrumentalization of urban space for financial speculation is nothing new, the post-pandemic rush to convert cities into objects of touristic consumption or tools of wealth preservation unfolds in digital spaces largely invisible to local residents—making the impacts feel even more arbitrary and invasive.

Local lifeworlds and “city rot”

But I digress—back to Osaka. After a day of Airbnb hunting, I was ready to find some locals. I ducked into a little eatery a few hundred meters down the arcade, hidden behind a waist-length purple curtain amid a stretch of lonely karaoke bars with Chinese onesan asking me to come in for a drink.

If you’ve ever seen Midnight Diner on Netflix, this place had similar vibes. Behind the U-shaped counter, the gentle-mannered master seemed to know most of the people there—an elderly couple, whom he passed an extra bag of food on their way out the door, a few middle-aged ladies who noticed my kakuuchi t-shirt and started listing off areas I should visit, and the young Chinese man next to me who had moved to Japan when he was two (When I returned the next evening, the master greeted me with a hearty Osaka “maido!”—welcome back!) Salarymen and a local hustler sat near the door nursing tobacco. I decoded the scribbles on the blackboard and ordered a draft beer and four dishes before finishing off the meal with a perfect egg-drop & plum rice porridge cooked in a steel pot. The bill was $15.

This, my friends, was Osaka bliss—delicious food, friendly people, low prices. The image of the city that tourists encounter online (hey ChatGPT, why should I visit Osaka? Osaka is worth visiting for its vibrant street food culture, friendly locals, and a perfect blend of modern energy and historic charm) is certainly rooted in reality. Do any tourists ever wander in here? I asked the master. He tilted his head as he sliced my sashimi. Every once in a while, but not too often.

Outside the doors though, there were plenty of tourists, surely staying in places like mine deeper in the neighborhood. Italian families with elderly parents in tow, young American couples, and German otaku emerged in groups from the dark alleyways and followed the light of their phones north through the gauntlet of karaoke bars. Those who didn’t give in to the temptation of the FamilyMart near the metro stop continued past the homeless encampment under the railroad tracks and onward into the salvation of Shinsekai: large picture menus of kushi-katsu and sushi in the supersaturated glow of a retro amusement park, originally built on the grounds of the 1903 expo—better known as that place from Instagram.

Reality these days mimics social media, and what stands out about mass tourism lately is how many people treat the cities they visit as an IRL extension of their feeds. I do not think we should meekly assign blame for this shift in the urban experience to an amorphous force called “technology,” as if there has been no agency behind the mutating relationship between physical reality and its digital twin. No, let’s be frank: it is the consequence of profit-maximizing decisions, mostly made in San Francisco since the 2010s, related to how symbols appear on maps and visual fragments get served to us as we scroll. Now we have to live in a mixed-up world where treasured small businesses get ruined overnight, travelers thoughtlessly book places next to brothels and still leave five-star reviews because meh 🤷♂️, and teachers get shoved out of their homes so folks who happen to have a stronger currency can enjoy an authentic experience of scarfing down re-heated takoyaki and those viral egg sandwiches next to the trash bins in front of 7-11.8 I’m sorry, but what the fuck is this?

What I don’t think it is is “gentrification,” at least not in the sense that most people understand the term—as a cycle of urban regeneration where the depressed arcade starts to fill with establishments catering to the newcomers, the urban fabric is re-stitched with new patches of cultural texture, and three or four stages later people look around at the hipsters selling overpriced art and doughnuts beneath fancy flats and go gee, this place sure got rich and sophisticated! The Airbnb-ification of Nishinari feels more like the city being picked over to extract value from the fading vibes of Japan’s postwar glory. Unfortunately, that trick only works once.

As Kyoto University philosopher Masatake Shinohara has written, the urban future will be shaped more by forces of ruination than development or renewal, a reality that our habitual language and mental models are ill-suited to describe and understand. We need new concepts (like “technofeudalism”) to describe how mass tourism and global flows of capital fit into the post-growth urban process. Airbnb-ification does not transform ruination into renewal, but introduces a different sort of disintegrative force. Perhaps we can borrow from recent discourse on “IRL” cultural manifestations of online brain rot and call this process “city rot”—local lifeworlds are not being renewed, but rather overwritten in befuddling ways by spaces that are textureless, devoid of meaning, or meme-ified, and tie the city’s fate to the arbitrary circulation of images online. What happens when the next disruption arrives—another pandemic, a stock-market collapse that crimps international travel, a change in the algorithm—and the tide goes out, leaving these spaces marooned in the shells of neighborhoods where local life has long since washed away? There must be a better way forward for the post-growth city than this.

Tokyo is drizzly and cool, a perfect season for quiet evening walks in the back streets. More to come soon on Labyrinth House, on Tokyo, on the expo…stay tuned.

Local community members took issue with a March article on Kamagasaki in Le Monde that framed recent events in the neighborhood in a typical case of mega-event driven gentrification and displacement.

Seeing Cocoroom for the first time in 2015 influenced how I thought about the social possibilities of post-growth neighborhoods, which evolved into my thesis and projects at Inari-yu Nagaya and Labyrinth House. Networks of post-growth urbanists being what they are, a former staff member of Cocoroom, Wataru, eventually found his way to Onomichi and is now a key member of the Labyrinth House team.

『万博を解体する』, p.9

In Tobita Shinchi, ostensibly forbidden intercourse is practiced under the guise of “free love” between a restaurant waitress and patron. Japanese cities are good at grey zones!

As an aside—Tobita Shinchi is immaculately clean. Walking the streets in the morning, when all but a few of the brothels are shuttered, everything appears to have been carefully scrubbed and tidied up.

The visa-acquisition purpose of Osaka Airbnb developments is easy to pick up on when scanning the registration records—in many of the multi-unit developments listing Chinese as a language in the rightmost column, each unit is owned by a different front company.

In June I was in Bologna, where the meme di città is mortadella.

Glad to see Cocoroom! One of the few places doing it right. Why can't that way of doing become a TikTok trend :-D

On my last visit, just as the Expo was getting rolling, I felt Osaka changed a whole lot, not just since pre-pandemic, but even in the several months since my last visit! The Airbnbs were one rapid change, also the seemingly high level of waste on technology in the public sphere: 100% dazzle, 0% useful-improvement-on-what-was-there-before.

Even though I agree with your sentiments here, it is difficult to wrap my head around the things that are happening in Osaka in particular.

Well, another reason, I think, to focus energy on (as you are) local efforts that cherish where we are, and who we are :-)

Great observation! I remember when I stayed next to Kamagasaki in 2013, I had no idea about the area and just saw a cheap hostel. I emailed my professor in Hiroshima, and he suggested "Check out Tobita Shinchi, but don't take photos, the yakuza don't like it." It certainly was a different Japan I encountered there.

I, too, wonder what's after the Airbnb-ification. Berlin is in a similar situation and while they did pass a law prohibiting using apartments only for short term rentals, it takes a long time to process all pending cases. In June, they announced, that 8000 apartments for short term rental (and other variations) were forced to become normal residential long term apartments again.

Taking the long view: More than a hundred years ago, residential buildings with huge apartments were built for the bourgeois. They included rooms for servants and such. Now, these buildings still stand and (if they got lucky) the apartments are shared by low income families or students. It's a different kind of gentrification, albeit very slow, it took two wars and the Berlin Wall to achieve it – and it looks to be slowly undone by capital moving now. However, this might shift once more.