Is a city alive?

From the rights of nature to the right to the city

Where does mind stop and world begin? Not at skull and skin, that’s for sure.

Life is as much undergone as done. We are constitutionally in the midst.

—Robert MacFarlane, Is A River Alive?

Robert Macfarlane’s Is A River Alive? asks what would it mean for our understanding of the natural world and our relationship to it if we saw rivers not just as ecosystems containing life, but as truly alive. In beautifully animistic prose, Macfarlane ventures to the frontier of the rights of nature movement, where rivers are treated as subjective entities that think, feel and are endowed with legal protections. The book also inspires a related thought experiment: is a city alive?

Like many good books, I encountered this one not through a screen, but in a particular place: arranged on a table among stacks of other books, at a storied bookstore near old universities in a city with enough readers to sustain many such bookstores. While I was in New York, I wandered into bookstores every few days and often let the shelves choose for me. On that day, the words on the cover spoke to me and I was in and out of the Strand in all of five minutes.

One of the consistent themes throughout Is a River Alive? is that life is a collaboration between the self and the world. Here is Macfarlane describing the moments before he descends a rapid in northern Quebec that nearly swallows him:

Then in a snap I realize it’s too much, too dangerous, I’ll need to line or portage my boat past this, and I turn to tell Danny, and then with a second snap the grey light of the overcast sun is flicked off as a cloud clears it, and the rocks and my eyes are flooded instead with bright-gold light, and the sudden warmth of that light takes the decision for me - for at the moment of choice, the business of choosing is almost always all done - and so I nod a yes, let’s do it at Wayne and Danny, and we walk back to the boats as if to an execution.

Reading such signs can be just as much a part of the practice of urban life, to sometimes surrender intention and let the streets pull you in unknown directions, to recognize the city acts upon the self as much as the other way around. I was reminded of times I’ve come across spaces on the verge of destruction during walks around Tokyo, talked my way inside, and felt drawn to save a particular piece of wood or object, and then a short time later, for that object to reveal its intention to be reused in a particular way in one of my renovation projects. There’s no enchantment in chalking these things up to random chance; I prefer see the objects or the city as possessing a spirit, and myself as their agent to carry some fragment of urban memory into the future.

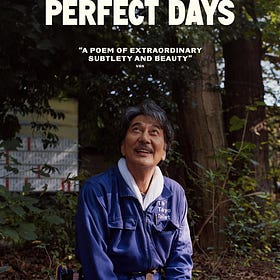

I explored the idea of urban life as a collaboration with the world most clearly in my review of Perfect Days, a piece that originally went out to a few hundred subscribers but has in the past few months has racked up hundreds of likes through the vagaries of the algorithm.

The analog wonder of "Perfect Days"

There’s a moment in Wim Wender’s Perfect Days when a young woman, presumably born in 21st century Tokyo, slips a cassette tape into a car stereo and hears an analog recording for the first time. She appears captivated by the revelation that recorded music can sound more textured and alive, perhaps more interwoven with reality, than the audio she typical…

“To be urban is to be analog,” I wrote in that piece, by which I meant that urban subjectivity should be rooted in an awareness of the self as interwoven with the environment and other people. Our ability to feel that way is being undone by material changes in urban space, and the way that digital technology increasingly mediates and shapes how we move through and inhabit urban places.

This is also why in my own projects in the city, I am preoccupied with the urban commons, a concept that exists not so much as a physical reality as a relation between people and their environment. As commons are encroached upon, as the city is rebuilt into spaces of prescribed function, the urban experience becomes shallow and passive, and the same death spiral Macfarlane sees in nature sets in: You raze the forest, you lose the cloud and the rain. You lose the rain and cloud, you kill the river. You kill the river — and all life leaves. This is why the destruction of Tokyo’s bathhouses has always felt to me like the killing of the city itself.

Although the ecological and moral stakes may seem lower, in a better world urban commons would be protected alongside rivers and other ecosystems from the state and market forces that objectify and extract value from them (see Lefebvre and Harvey). The city’s aliveness does not simply equate to superficial measures of economic activity or density of use, in the way that an Ecuadorian cloud forest is profoundly more alive than a eucalyptus plantation, or how the cascade of one of Macfarlane’s sentences is animate in a way that a chatbot’s limp string of regurgitated tokens never will be. Unfortunately, just as the natural world and human culture are being degraded, so too does much contemporary development relentlessly extract what remains of the city’s life-force in the pursuit of narrower purposes.

In Japan, we are blessed with another clear piece of evidence of the city’s aliveness: festivals. Which is a better mental model for explaining how locally rooted rituals and cultural traditions persist across centuries and generations: that people animate the city, or that the city animates its people? At least when I participate or am immersed in streets that overflow with sudden vitality, it makes me feel like Macfarlane’s young son when asked to weigh in on the adults’ debate over the life of rivers—why ask such a silly question? of course a city is alive.

The great thing about a festival is how, for a limited moment, it reveals latent possibilities of human sociality, and opens a portal onto another way the city can be. Festivals are thrilling because they suggest there are indeed escapes from the deadening of the city, and answers to the problem Macfarlane identifies: somehow we need to find new kinds of imagining, new ways of being that will leave us less alone in this world…our aliveness, as well as all life that lies beyond the human, is at stake in this.

Valuing urban commons enough to protect them from the market and political swings feels ... right on the money, as it were.

Definitely we can apply your sentiment to so much in Japanese cities. In general, to all the small old shops that serve so many critical social functions to their neighborhoods which have always (and should) go un-monetized. Different levels of value.

Speaking of Macfarlane, we fell in love with his writing during my school days in Edinburgh, a city which definitely also has some wild festivals. Hogmanay was a favorite. No spectators allowed. Everyone parades through the streets together with huge flaming torches until reaching the top of Calton Hill. It felt at once primal, peaceful, and surreal.

Anyway, thanks for this one.

I loved reading this! Is a river alive is also on the top of my to read list, this has inspired me to pick it up on the weekend, thank you!