The Line was the zenith of our age of insanity

Look on my works ye Mighty, and despair!

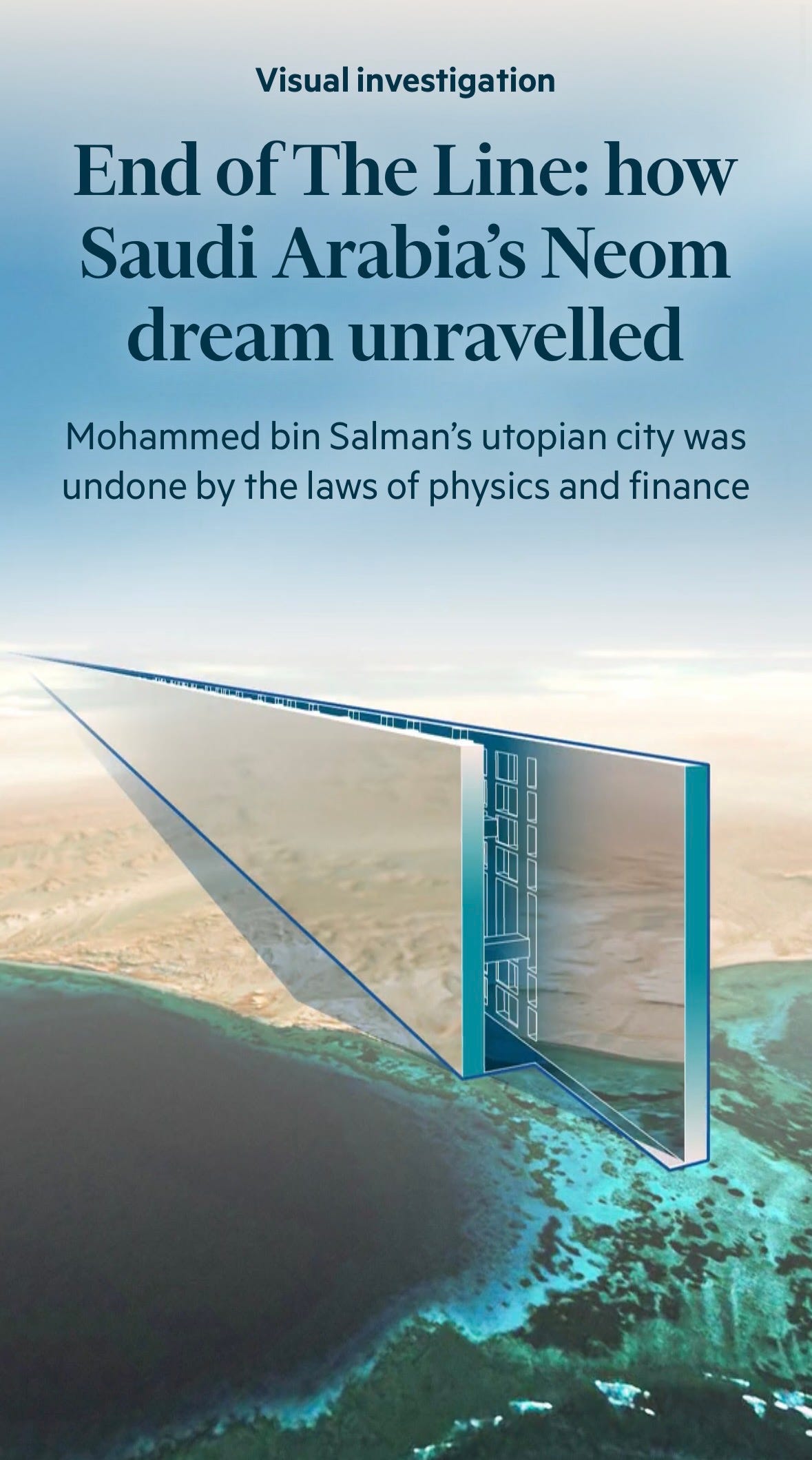

Future histories of these unreal times will need to include a paragraph on The Line. It was the ultimate embodiment of the spirit of our age, when crypto grifters co-opt nation states, billionaire boys fling their toy rockets to the heavens, and tech CEOs predict data centers will soon smother the Earth. Somewhere out in the Saudi Arabian desert, a mad prince with a bottomless sovereign wealth fund actually carved a 150-km gash in the sand, and exclaimed that he would build a 500-meter tall, mirror-glass-clad linear city and fill it with 9 million people.

Well, surprise: earlier this month, the FT ran a brutal piece by Alison Killing full of quotes from insiders rushing to escape the blast radius of a project imploding from its own engineering and financial hubris.

When construction began three years ago, The Line was meant to be a symbol of unstoppable momentum: transformative urban living without traditional streets or cars, powered by renewables, running uninterrupted from the Gulf of Aqaba to the Hejaz mountains. It would be the centrepiece of Neom, the futuristic metropolis through which Prince Mohammed intended to prove the scale of his ambition as Saudi Arabia aims to transition from oil to a digital economy.

“They say in a lot of projects that happen in Saudi Arabia, it can’t be done, this is very ambitious,” said Prince Mohammed, known as MBS, in a Discovery Channel documentary about The Line that first aired in July 2023. “They can keep saying that. And we can keep proving them wrong.”

But as the designs advanced, his dream collided with reality. The Line’s own architects began to question whether the structure could ever be built as imagined. Costs ballooned, timelines slipped and the foreign investment that Riyadh had banked on failed to materialise.

Today, with at least $50bn spent, the desert is pock-marked with piling, and deep trenches stretch across the landscape.

If your algorithm is calibrated anything like mine, you’ve probably seen Neom ads plastered across the internet over the past few years. If you are part of the reality-based community, you also may have wondered about a few minor details, such as where the nine million residents would come from, how they would source 60% of the world’s steel output or more than the planet’s entire production of cladding, or—please excuse my paltry imagination—how a line could possibly be a more geometrically efficient shape for a city than a circle.

“For too long, humanity has existed within dysfunctional and polluted cities that ignore nature”—The Line intro on YouTube

The cornucopia of fanciful development projects announced under MBS, which are rapidly bankrupting the Saudi investment fund, are easier to understand when you realize that to a large degree, they are engagement farming masquerading as urban design. Are you an up-and-coming, extremely online autocrat who wants the world to know that your kingdom is going to be the next big thing? The netizens of planet earth have a hard time looking away from hubris so breathtaking that it can be seen from space.

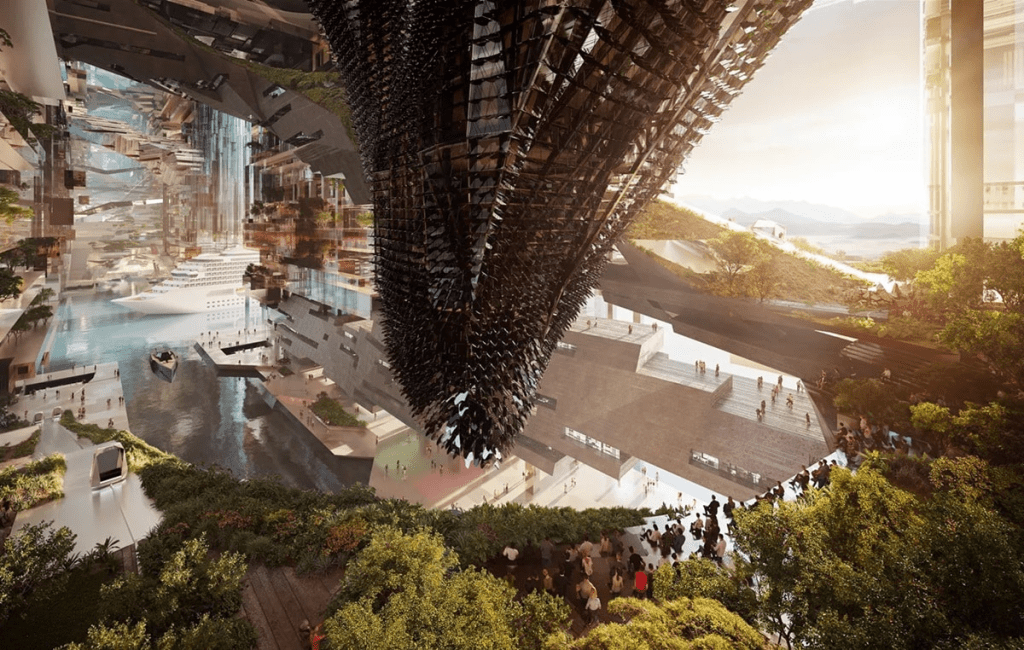

Thus untold treasure has been squandered according to a digitally-driven circular logic: try to bend the rules of physical reality to resemble eye-catching video-game worlds, in an effort to capture more attention in virtual spaces. Top-notch architecture, design, engineering and public relations firms were happy to play along for a fat payday, while the project’s mouthpieces went to Davos to sell the bright future being built in Saudi Arabia before the world’s assembled elites. Silicon Valley oligarchs, fed up with the civic process and high on their own supply, looked on in envy as they plotted their own desert utopias and grew convinced that progress was more compatible with autocracy than democracy. Now all this fantasizing has turned out to be a gust of hot desert air.

Most of the professionals involved will slink away to work on new projects elsewhere. But next time you open the Times and see Michio Kaku extolling the wonders of parallel universes, remember that in this one, he was happy to do sponcon for a scheme so obviously flawed that it should discredit the predictive powers of any futurologist willing to associate with it.

Perhaps the path to credulity about Neom was paved by the fact that an extremely absurd, superlative city has already risen from the Arabian sands. Dubai is an instant metropolis that revels in its own fakeness, and is always pushing the envelope of financial possibility. Couldn’t The Line similarly defy its critics?

“There is the idea of a city, and the city itself, too great to be held in the mind,” observed the writer George Saunders after visiting Dubai two decades ago. Despite its ostentatious artificiality, Saunders was surprised to discover Dubai was just an another ordinary city full of chatty taxi drivers, shady businessmen, and desperate strivers. “No place works any different than any other place, really, beyond mere details. The universal human laws—need, love for the beloved, fear, hunger, periodic exaltation, the kindness that rises up naturally in the absence of hunger/fear/pain—are constant, predictable, reliable, universal.”

Sheer physical and financial impossibility may have killed The Line, but it was always doomed by the assumption that universal human laws could be tossed aside and people would thrive in a sci-fi prison sandwiched between two panes of glass, as if trapped inside their phones. Put vast financial resources in the hands of a dictator addicted to virtual worlds, and he can raise battalions of marketing consultants, Hollywood art directors and Western thought leaders to stoke his ego, and armies of migrant laborers to sink piles into the desert. But invent the future of cities he cannot. The Line’s demise begs the question of what other grand schemes in this age of unreal promises may soon unravel.

The plan has sickened me from the start. Good riddance.

What a monumental waste of money and manpower. Just imagine how much good that money and manpower could have done. Then again, it is unlikely that Saudi Arabia would use its wealth to do good…