Is the best tech for learning Japanese 20 years old?

I miss the cognitive friction of my old electronic dictionary

More on urbanism coming soon, but some recent thoughts about language and technology came to mind after reading Marco Giancotti’s essay on how people in Japan (including me) have lost the ability to write many kanji, mostly due to over-dependence on smartphones. I was particularly interested in his personal experience of learning Japanese beginning in 2006, the same year I went to Niigata as a high school exchange student. In a few important ways, I think the mid-2000s were sort of a technological sweet spot for learning Japanese.

Like Giancotti, my approach to the language was centered on maniacal kanji acquisition. Each day during classes, I scribbled characters from a small learner’s dictionary into notebook after notebook at my desk. I tried to learn about ten per day, and review what I recently learned. By the end of the year, I had become literate enough to read and write about 1,800 characters and thus comprehend a decent amount of the written word.

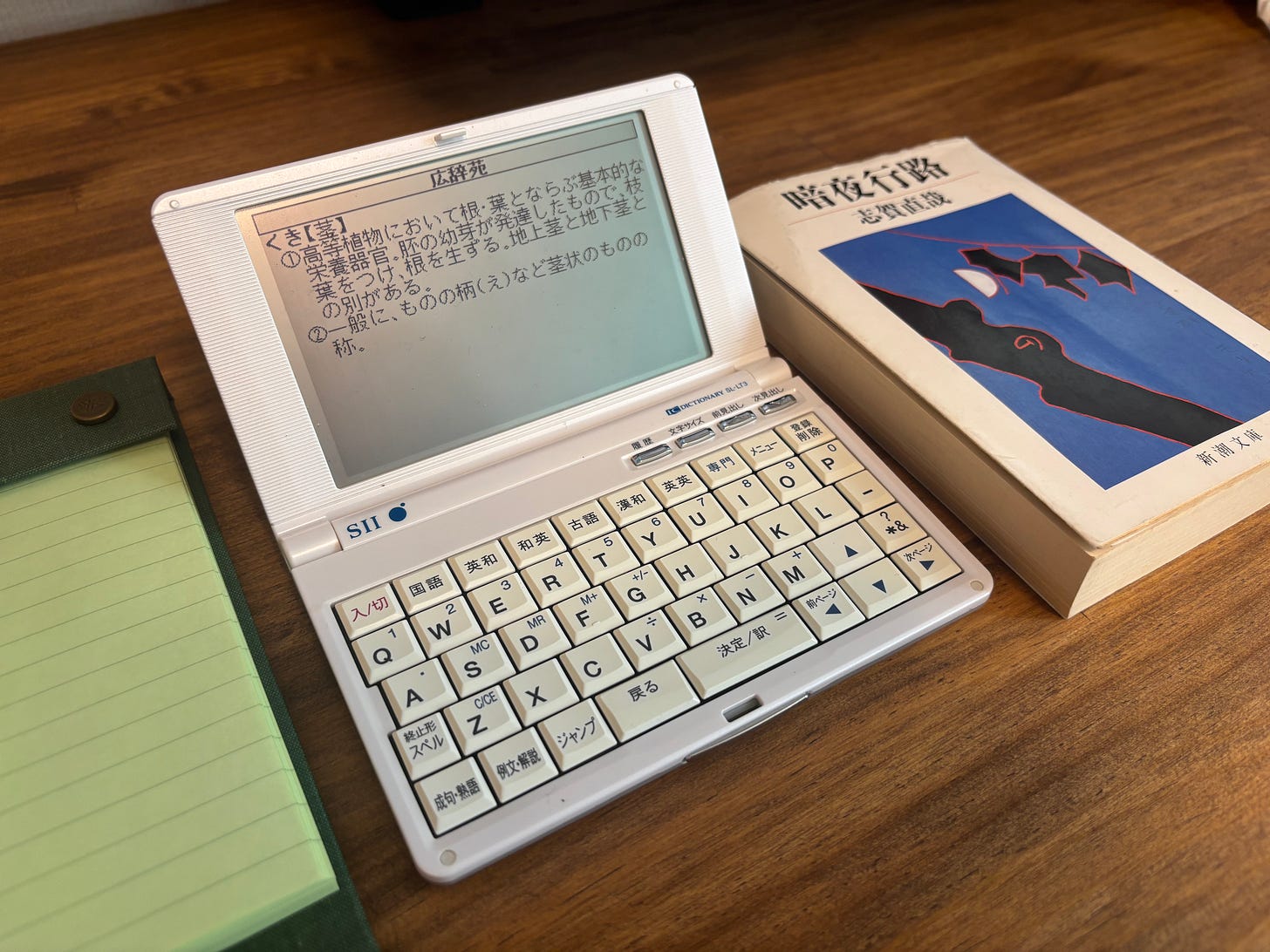

Besides my notebooks and texts, my most valuable tool was an electronic dictionary, or denshi jisho. By the early 2000s, these little pocket-sized gadgets had become standard-issue items for Japanese high school students, and for good reason: previously, a serious student needed not just a kanji dictionary, but also bulky Japanese, Japanese-English, and English-Japanese dictionaries.

I got rid of my denshi jisho sometime in college in the early 2010s, replacing it with a dictionary app on my iPhone with all the same content. Recently, after growing tired of the endless distractions that co-inhabit the screen while using it to read a difficult Japanese novel, I re-acquired my old electronic dictionary for about a thousand yen on Mercari. Mine was a mid-range model in 2006, original retail price of ¥36,000 ($300), with an aluminum and plastic clamshell enclosing a little pocket sized keyboard and monochrome screen that turns on almost instantly.

As a learning tool, this device has just the right amount of cognitive friction. To look up an unfamiliar kanji, let’s say 茎, you would first enter the number of strokes in the radical, in this case the three lines on top representing grass. After finding the right one, enter the remaining number of strokes, 5, to narrow down the results to the entry in the kanji dictionary that reveals the readings: kuki or kei.

The real step change of a denshi jisho was the ability to “jump” to the J-E dictionary for the English definition (“stalk”), or follow my tutor’s advice and go straight to the Japanese dictionary definition: “one of the basic nourishing organs of tall plants, along with roots and leaves…” The recursive process of searching and jumping reinforced literacy, not just because you had to trace a character in your mind to count strokes, but due to constant exposure to related kanji and words.

This cognitive exercise has been steadily eliminated by the convenience of technology that has come since. Some of the more advanced dictionaries in 2006 already had stylus input, obviating the need for radical-based lookup. Then came OCR scanners and smartphone apps that could effortlessly recognize characters without the need to reproduce them. Finally, where we have arrived today: copy-paste into the chatbot prompt, the blackhole into which literacy goes to die. Mystery in, meaning out.

Friends tell me a well-prompted AI can be a great language tutor. In my intermittent forays into Chinese, I’ve used grammar textbooks and readers as I did with Japanese, but also appreciate the functionality of an app that integrates text with audio and dictionary. Playing around with ChatGPT, I see it can generate informative answers and convenient vocabulary lists for any inquiry. Then again, I learned Japanese in ten months; I’ve been dabbling in Chinese for a decade and still don’t speak it. I get a little hit of dopamine from feeling like I learned some Chinese, and then…I go do other stuff on the internet. 學得很好!Granted, I was more motivated and disciplined then, but if the question is not are these tools useful?, but whether I would prefer to learn Japanese in today’s technological environment instead of twenty years ago, the answer is an unequivocal no.

2006 technology—or rather its limits—let me tap into that now elusive substance of solitude. I had hardly any direct access to English information beyond a ten-minute rebroadcast of the BBC during breakfast, and thus no escape besides trying to read and communicate with the world around me. This solitude was not unpleasant, it made that year feel valuable and distinctive in a way that time had never felt before.

Like my siblings who went abroad five and eight years before me, I stayed in touch with home through short internet sessions on public computers, postcards, and a very occasional call. A month before I went back to Denver, I remember loading the NYT homepage on the PC in the station waiting room and seeing Steve Jobs holding up the first iPhone. By five or eight years after me, that degree of immersion was rendered functionally impossible by social media and smartphones.

I imagine the modern-day exchange experience feels less like the distinctive block of time I enjoyed, and more like how the rest of life is now—stuck between a frictionless digital world of familiar or irresistible information in an endless stream, everywhere, all at once, and a social world where individuals aren’t making friction with others at all: public spaces full of people facing their phones or with podcasts in their ears, teens no longer throwing parties or hanging out as much, the list goes on.

Of course, the implication of today’s digital technologies, especially generative AI, is that multilingualism is obsolete. The just-announced Google Pixel phone claims to offer live interpretation of phone calls, suggesting a future in which language learning is a hobby for parasocial consumption of subcultural content rather than a social means of communicating with other humans.

As mainstream culture becomes post-literate, it seems likely that learning foreign languages and cultures will also become one aspect of cultural resistance to pervasive tech mediation of our lives. So alongside the trend of people downgrading to dumbphones, I invite you to join my denshi jisho revival. The potential for humanizing experiences—reading foreign novels, mastering languages, forming relationships across cultural divides—still remains, we just have to be more maniacal about keeping technology at a healthy distance.

In related reading, I appreciated this article about the impact of AI on translators. I happen to earn about 75% of my income from translation in a niche that has so far been economically unaffected, but clearly that is not the case for many of the people whose experiences are gathered here. As Merchant observes, while machine translation is nothing new and has not surpassed humans, recent AI hype has created a permission structure to start cutting human translators out of the process. There will surely be more translated content than ever before, but in translation as in immersion and culture at large, I have a hard time believing that’s an improvement.

I never had a denshi jisho back in the day, but I did finally get a Pomera recently (which has one built in) and yeah, there is something to be said for the cognitive friction that you get from a (nearly) single-purpose device.

https://www.multicore.blog/p/pomera-dm250-review-king-jim

I think having access to iPhone apps dramatically helped my Japanese learning in the late 2000s (I came here in 2008), because I probably wouldn't have had the patience to hand-write flash cards and so on, but I suspect you're right that we're overcorrecting. I'm certain I wouldn't have had the same motivation to actually learn the nuts and bolts of the language if Google Lens and ChatGPT had been around.

I went to a press conference today and used a Pixel to record and transcribe the Japanese speech in real time so that listening back is a matter of editing rather than writing. That's a meaningfully useful feature that has saved me countless hours over the years. The live phone call translation, though, just makes me very uneasy, even though there's also an accessibility case to be made.

Thanks for the app links. I’m struggling these days to find a proper tool to read a kanji or a word I don’t know. So, I may check those . 20 years ago I tried to use electronic dictionaries also but somehow the old printed heavy vocabularies served me better…